Deciding what to keep and what to relegate to the yard sale pile is always a source of contention for Myra and me. She has a simple philosophy. If it has no immediate use, dump it. Terse. Laconic. Succinct.

My reverie is interrupted. I hear Myra's voice from the corner of the dusty attic Clearly she has discovered another of my treasures to dispose of.

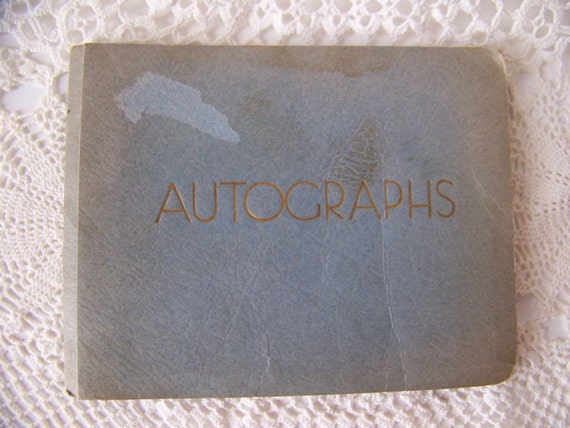

"What's this," she says, holding up an album that has been carefully wrapped in plastic and tied with a string. I recognize it immediately. My heart skips a beat.

"Nothing important," I reply. I don't know why I lied. After all, it is nothing ore than an autograph album from an elementary school ceremonial. It was our custom in those days, to inscribe some epigram of farewell in one another's book. Today was graduation day. We were going on to High School.

Myra undid the string, sat on an orange crate, and began leafing through the album.

Perhaps it wasn't guilt. I felt that something private, something sacrosanct, was being invaded.

It was important, perhaps the most important: The written exchanges of farewell was a rite of passage and the end of childhood years. It was more than a matter of self-image, on how many students wanted to exchange amenities with me.

"Who was Estelle Abrams," came the voice from the orange crate.

"A mousy little girl," I said.

"Were you really?" added Myra.

"Really what?" I answered.

""The cleverest, she wrote, 'to the cleverest in the class.'"

I did not answer.

"And Selma Rabinowitz?" Myra followed up.

"Certainly not mousy," I admitted. 'Don't do anything I wouldn't do,' Selma had written.

Selma had grown to a challenging presence during school. A daughter of Eve with all the primordial attributes intended by the Creator. But she hadn't been Elise.

These are reflections of memory matured by the passage of time. There is no possibility of comprehension by the mature mind of the unexplored internal world of youth; of boys awakening from the slumber of childhood, thence to an epiphany of beauty that comes once in a lifetime.

On that day I suffered the importunities necessary to the ritual. All else was peripheral, wearisome. I was waiting for Elise.

The class comedian and curse of the perpetually hysterical Miss Hurley, who taught Geography, made his mark. What he wrote and what Oscar Schaeffer scribbled eludes me as of no consequential. Harold Steckel, fat and elliptical in shape, plagiarized Shakespeare, to wit:

"Is this a dagger which I see before me?" hardly appropriate to a graduation ceremony. Bernice Cohen held my hand between her overly warm palms. Still, Elise did not come.

"Honey," came the voice from the orange crate. "Who was Elise?"

"Just another girl," I said.

I remembered the shy, tentative approach, her album offered to me as if she anticipated rejection. I do not recall what I wrote.

"Goodbye is a very sad word," was her phrase in mine.

"Honey?" came the voice again from the crate.

"Yes, Myra." I held my breath.

"Was Elise pretty?"

"She was, Myra."

"Prettier than me?"

No comments:

Post a Comment